|

After

its remarkable successes with the ZX81

and Spectrum,

it seemed that Sinclair Research could do

no wrong. Its next computer, the Sinclair

QL (or "Quantum Leap"),

was promoted as a revolutionary breakthrough

- the first 32-bit home computer,

costing under £400. Great things were

promised - reliable twin microdrives, multitasking,

networking, a proper monitor, a huge 128KB

of memory backed up by a Motorola 68008

processor. The optimistic mood was summed

up by Sinclair's television adverts, showing

a scarf-wearing Sir Clive leapfrogging over

a line of competitors' inferior products.

It

was not to be, however. The early promise

of the Sinclair QL was rapidly undone by

the disastrous technical and production

difficulties which the machine encountered

in its first months on the market. As had

happened on so many previous occasions,

Sinclair's delivery systems and quality

control were seriously deficient; frustrated

owners waited months for their machines

only to find, in many cases, that when they

eventually arrived they did not work properly.

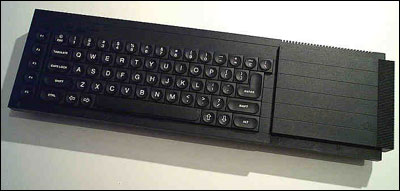

Even

those that did work initially came with

an unexpected addition: a "dongle"

(right),

a small board hanging out of the

rear of the machine, containing the ROM.

Sinclair's rush

to get the QL onto shop shelves meant that

the ROM had not been finalised when the

machine went on sale. As a result, it had

to be mounted on an external board - hence

the infamous dongle. Even

those that did work initially came with

an unexpected addition: a "dongle"

(right),

a small board hanging out of the

rear of the machine, containing the ROM.

Sinclair's rush

to get the QL onto shop shelves meant that

the ROM had not been finalised when the

machine went on sale. As a result, it had

to be mounted on an external board - hence

the infamous dongle.

Despite all the problems, the QL did manage to achieve sales

of 100,000, though this was far less

than Sinclair had hoped for given the machine's

specifications. The ZX81

and Spectrum

had, by comparison, sold millions. To some

extent, this was a result of the way in

which the machines were marketed. The ZX

machines were unashamedly aimed at the home

market and overwhelmingly used as games

machines. The QL, on the other hand, was

pitched very much at business users - the

number of commercially available games produced

for the machine was negligible.

But

Sinclair was unlucky in his timing. The

release of the non-PC compatible QL happened

to coincide with the rise of the Microsoft-Intel-IBM

standard. At the same time, the cost of

PC hardware (notably mass storage devices)

fell to a point where the QL's price advantage

was eroded. Within a couple of years, businesses

had adopted a standard setup - IBM-compatible

PCs running MS-DOS - and the market for

a non-standard business computer like the

QL simply vanished.

After

the 1986 takeover by Amstrad of Sinclair

Research's computer business, the QL was

quietly dropped. However, the QL's

technology survived for a while in a number

of different guises, notably as the ICL

One

Per Desk.

The

QL, however, had a much more lasting legacy

in a wholly unanticipated way. In the mid-1980s,

a young Finnish programmer named Linus Torvalds

upgraded from his VIC-20 to a Sinclair QL

to learn advanced programming. Years later,

he recalled:

[I] was eventually able

to get a Sinclair QL and get some real

programming done under a multitasking

(albeit somewhat weird) system.

On the Sinclair QL I continued

to program in assembly (the QL BASIC (SuperBasic)

was ok, but I wasn't interested), and

I wrote various more-or-less useless programs

(ranging from a FORTH compiler and an

editor-assembler system of my own to Pac-Man

to a MSDOS compatible floppy disk driver).

The QL was a fun machine, but there weren't

very many of them in Finland, and although

I was generally happy to write my own

programs (still am), it did teach me to

buy hardware that actually is supported.

[Linux

News issue 3, October 18-26 1992]

In March 1991, Torvalds

upgraded to a 386 PC, using the programming

knowledge which he had gained on the QL

to produce a cut-down version of the UNIX

operating system which he nicknamed Linux.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Back

to top

|